Spotify has been under fire by many music artists, influencers, and creators after announcing new policies related to royalties and payments beginning Q1 2024. I was bombarded with videos and articles lamenting these changes, with every video further burying Spotify . I decided to read the changes myself and after reading the new policies, alongside the reasoning behind them, I was dumbfounded as to how Spotify was the supposed big, bad corporation so many were claiming them to be.

The following policies will be introduced at the start of 2024:

- All tracks will are required to reach a minimum of 1000 streams within a year in order to be paid a royalty.

- Labels and distributors will be charged a penalty for delivering fraudulent streams.

- Functional tracks, such as white noise or environmental sounds, will abide by a new minimum play time (longer) in order to earn a royalty.

Based on these new policies, Spotify is being labeled as greedy, anti-artist, and everything wrong with the music industry by numerous people, one notable critic being Anthony Fantano, otherwise known as TheNeedleDrop. Other YouTube channels also weighed in, such as Curtiss King, TopMusicAttorney, and Weaver Beats. Even TheYoungTurks had a segment on their channel where they discussed the changes. I watched their videos, as well as many others, and by far the most reasonable conclusion came from Damian Keyes, who was more cautious about jumping to conclusions and tried to see why these policy changes were even being drafted. Before I give my opinion on the matter, I think it’s important to refresh our memories to gain a better perspective.

Vinyls, Cassettes, and CDs Oh My

Before the digital age and the mass adoption of the Internet, physical media was the primary way to enjoy music. Without having the actual media in-hand, the average person was relegated to live performances and radio. Artists were at the whim of big labels investing their resources into promoting, showcasing, and distributing their work. In return, big labels made a fortune. Of course, a small piece of a big pie is still a significant amount of money but some would argue that the majority of the money generated should go to the artist, not the people in suits. Either way, this was the industry standard from the introduction of vinyl records all the way up to the dawn of the compact disc, and would have continued had the labels maintained control of the supply.

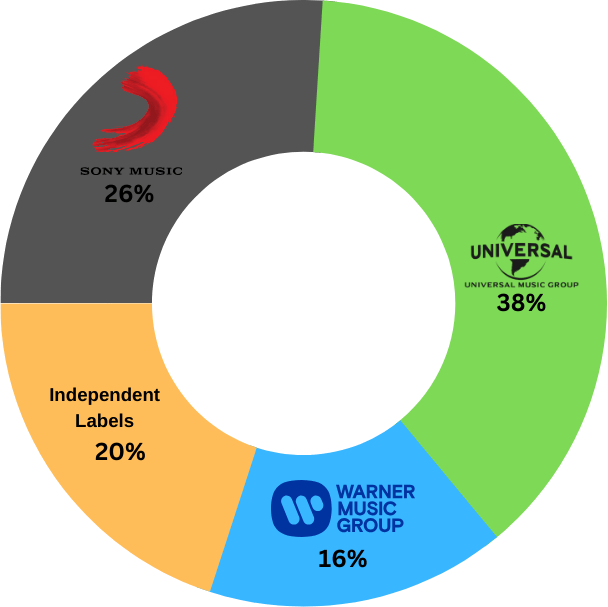

As of writing this there are three big labels: Universal Music Group (UMG), Sony Music Entertainment (SME), and Warner Music Group (WMG). Together they own about 80% of the music industry, with the last 20% comprised of a bunch of small independent labels. It might seem like you’re more familiar with other labels not listed, but more often than not it’s because they are owned by one of the big three. Does your favorite artist release music under Interscope Records? Well, they belong to UMG. What about Columbia Records? SME has that one. Surely not Atlantic Records, right? Wrong, they’re owned by WMG.

And because of their immense influence in the space, they can dictate the flow of who and what becomes popular. Additionally, they can lure unsuspecting artists with generous promises but then draft contracts filled with a bunch of legal jargon, leaving the artists receiving the smallest share of the money their work generates. This is as true now as it was back then, but with a key difference: making it on your own is easier now than ever before.

The SS Napster

Around the turn of the millennium, the music industry was disrupted by a company called Napster. It was a peer-to-peer file sharing platform that allowed the distribution of files, particularly MP3s. Even though other similar services existed before it, Napster featured an easy-to-use UI that made it simple for anyone to use. At the height of its popularity, Napster had about 80 million users. It wasn’t too long until the big labels and popular artists noticed that people could easily share their work without having to pay them. Piracy was the biggest threat the media industries ever faced, and they weren’t going to sit idly by and lose everything they worked hard to keep.

Metallica sued Napster after one of their unreleased tracks was leaked and downloaded thousands of times. The Recording Industry Association of America (RIAA) would later claim that Limewire, another peer-to-peer file sharing service similar to Napster, owed the music industry “72 trillion dollars worth of damages.” That’s 12 trillion more than the gross domestic product of the entire planet. They created public service announcements like Don’t Copy That Floppy and You Wouldn’t Steal a Car, in hopes of convincing (or scaring) the public to not share their media online. They lobbied politicians to push new legislation that would protect their property online, most notably the Digital Millennium Copyright Act (DMCA).

Some artists, however, saw piracy differently. To them, piracy was free promotion through sharing and word of mouth on a scale never-before-seen. If someone downloaded their music, it wasn’t a guaranteed lost sale because they might not have bought it without first listening to it. Often times, it actually led to an increase of sales due to the increased exposure. Artists could now reach the masses without requiring radio play, magazine articles, news coverage, or touring and venue deals. Limp Bizkit, a popular band in the late 90s/early 2000s, famously supported piracy and signed a deal with Napster to promote 23 free concerts.

There’s a ton of data available on all the aspects of piracy and its impact but it seems to have a major trend: piracy seems to benefit independent or smaller artists while hurting the large, powerful labels. The music industry giants were fixated on equating an illegal download to a lost sale. But for small artists, their music wasn’t their main source of income. They generated most of their money through playing music gigs and selling merchandise. And even big artists were at the mercy of how much money the labels wanted to share with them, as very few owned any of the rights to their music. But what if instead of fighting piracy, the music industry embraced the digital age?

Stream Me Up, Scotty

Music labels had to adapt and began selling music online. Selling digital versions meant less manufacturing, shipping, and stocking costs. It also made it easier for labels to distribute their content as they could point to a select-few digital distributors, like iTunes, as the place to find their music. This obviously didn’t stop piracy but it did help recoup some lost sales as CDs quickly became a thing of the past. But as the Internet grew and matured, it created new opportunities not possible before. Most people now had access to broadband internet speeds, making browsing seamless and buffering a rarity. Smart phones became the norm and the mobile experience was constantly being improved. The Internet was now accessible anywhere, anytime.

Although we had a taste of what streaming music would eventually look like, it was confined to small storage devices like the iPod, and would only consist of music you already downloaded. If your music catalogue was in physical media, like CDs, it meant you had to rip each CD to your PC. This process wasn’t straightforward and took a long time. And if your PC died or you wanted to upgrade to something else, it meant having to redo the entire process again. There was too much friction for most people to maintain a digital database of all their favorite music.

Streaming changed all that. People could now watch or listen to their favorite media without having to store it locally. As long as they had an internet connection, they could access all the content they wanted. This was a big opportunity for a service to try and fulfill, and many took notice. Among the major players, Spotify dominates with 35% of the music streaming market share. Apple Music is the next biggest with 19% of the market, and Amazon Music sits right underneath at 15%. The streaming market grows every year, especially as these services open in new regions like India and Africa.

Improvise, Adapt, Overcome

So, now that we took a trip down memory lane, is the recent outrage justified?

Does Spotify pay artists well? Well, that’s complicated. Spotify pays artists based on a pro-rata system, which means that the total revenue pool is divided among all the streams on the platform, according to their share of the total streams. The more popular an artist is, the more money they make per stream. This can also lead to smaller, less popular artists earning less per stream. But this system is to appease the large labels, which Spotify has to maintain for business. Like it or not, the reality is that most people don’t listen to the small artists on the platform and losing the big names could quickly lead to other services taking market share. There’s also the fact that less total streams means less revenue generated to share with the small artists, so it’s a lose-lose either way.

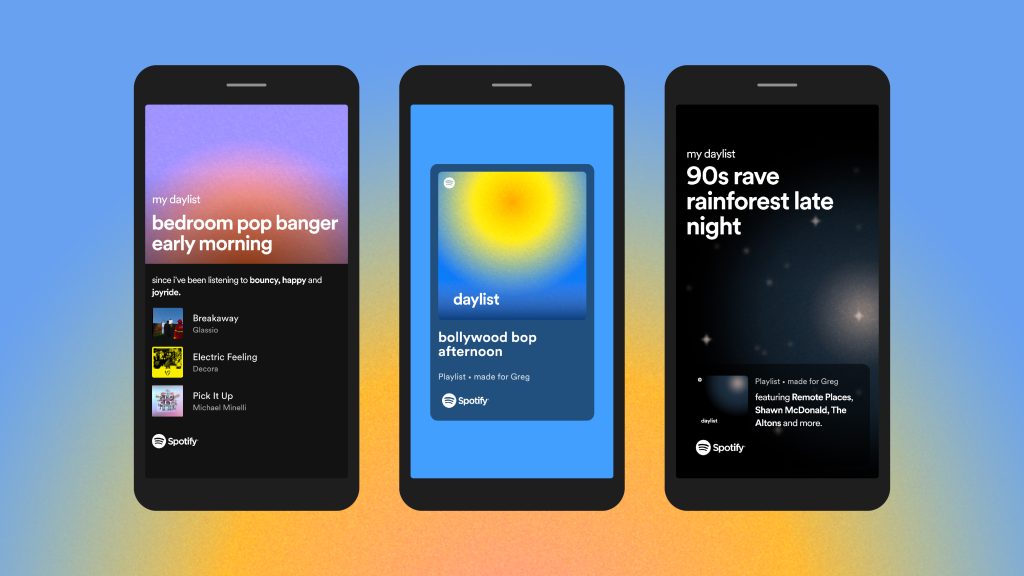

But how much Spotify pays isn’t everything. We need to remember how little artists there were before streaming services became a staple. At least Spotify allows artists a chance to grow and remain independent, all while giving them the tools to grow their brand and expand their reach. They don’t impose exclusivity and allow artists to monetize through other platforms, like Bandcamp and Beatport. They give artists the ability to post their tour dates and links to their merchandise. And last but not least, their algorithms for promotion and playlist generation is unrivaled and benefits both the artists and listeners.

These new policies won’t change much for legitimate, small artists. This is similar to other requirements imposed by the likes of YouTube and Twitch, where they won’t allow creators to monetize their content unless they meet a minimum threshold. Their income from streams is already non-existent if they cannot break 1,000 streams. It also tackles another issue that Spotify faces which is botted and hacked accounts streaming low-effort, fraudulent tracks that try and game the system. These are tracks that are usually 31 seconds long, contain very little in terms of sound, and are mass produced to crowd out legitimate competition. This boosts the scammers streams and qualifies them for royalties, and since Spotify pays pro-rata, it means less money reaches actual artists.

Spotify is not the enemy of the musicians, but rather an ambivalent partner to the big labels. While it would be commendable of Spotify to fight against them, it isn’t realistic. The average listener would rather continue listening to the most popular artists than boycott. It would be better to direct the hate towards the big labels that strong-arm the industry with their influence. Any meaningful change to help small artists would require taking on the big guys, and I don’t believe it’s Spotify’s duty to sacrifice their company for the sake of ethics. It would set us back so many years, to a time where it was incredibly rare for an artist to make it on their own.

I’ll end with this. Spotify has allowed for more artists to exist and thrive off of their work without the help of big labels. Artists have access to an enormous audience, can be featured in playlists generated and promoted by Spotify, and receive compensation. Sure, the compensation isn’t the best but it’s better than nothing. Ultimately, if the artist disagrees with the new policies, they have every right to remove their work from the platform.